Innovation in the Balkans – Part I – Northern Croatia and Slovenia

The region known as the Balkans, located in southeastern Europe, runs from the Southern Alps to the Greek peninsula and is surrounded by the Adriatic, Ionian, and Black Seas. The region is a crossroads of civilizations, with major influences from ancient Rome to the west, the Austro-Hungarian Empire to the north, the Greeks to the South, and the Ottoman Empire (Turks) to the southeast. In the modern era, the Balkans have been the site of numerous armed conflicts, with the most recent battles occurring after the breakup of the former Yugoslavia in the early 1990s. Indeed, one of the greatest military conflagrations of the twentieth century, World War I, saw one of its triggering events occur in the middle of this region in the city of Sarajevo (more on this later in Part II).

The region is in the news as of late, with the announcement of an agreement between Greece and the former Yugoslavian Republic of Macedonia in which the latter will change its name to North Macedonia so as not to be confused with the Greek region “Macedonia.â€Â This seemingly innocuous name change has been the source of consternation for decades, highlighting the historical tensions in the Balkans. Greece has used the conflict over the name as grounds for blocking Macedonia’s entrance into the European Union and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization.

I recently traveled to several countries in the Balkans as part of my ongoing quest to find unexpected examples of innovation. My hypothesis, that innovation thrives in regions where multiple civilizations interact, proved accurate in this case. This is the first of two articles on the Balkans. Part I focuses on Northern Croatia and Slovenia, while Part II will address coastal Croatia (Dalmatia and Istria) as well as Bosnia-Hercegovina.

Croatia

Croatia is an oddly-shaped country, vaguely resembling a boomerang or crescent moon. The country has mountainous terrain in the north as well as an extremely long coastline on the Adriatic Sea, with hundreds of islands running from the border with Italy near Trieste in the north to the border with Montenegro in the south. Croatia was the second of the Yugoslavian Republics to declare independence in 1992 and it suffered through a multi-year war with the former Yugoslavian Republic of Serbia to gain its independence. Croatia today is a member of the EU, has a successful tourism industry, and is transitioning to the Euro currency in 2020 as part of its ongoing plan to become fully integrated into the EU.

Tesla in Zagreb

Plaque Commemorating Telsa’s Visit to Zagreb

With a name that is now synonymous worldwide with innovation, Nikola Tesla is perhaps the most famous scientist and inventor from Croatia. Born in 1856 in the Croatian village of Smiljan, Tesla’s presence is widely seen in the city of Zagreb, particularly in the Technical Museum (Tehniki Muzej), also referred to as the Tesla Museum. Inside this building, one finds a permanent exhibition called the Tesla Cabinet that contains a number of reproductions of Telsa’s famous inventions and experiments involving electricity. Outside the museum, one can also stroll down Nikola Tesla Street (Ulica Nikole Tesla) as well as find a plaque commemorating Tesla’s famous visit to Zagreb in 1892.

In town to visit his ailing mother, Tesla inserted himself into local affairs by meeting with government officials to propose that Zagreb become the first city in the world to implement Tesla’s innovative hydroelectric power generation system. Tesla espoused the benefits of the system but faced a skeptical City Hall in that politicians had already made major investments in a network of gas lamps for lighting their city. Zagreb decided to pass on Tesla’s proposal, so the Croatian inventor ended up implementing the first hydropower system in Buffalo, New York. Zagreb would not get electric power until 1904, fully twelve years later than what might have been possible had they heeded the advice of the inventor.

Gas Lamps in Zagreb

Innovation Thoughts – The story of Tesla’s attempt to install his first hydropower solution in Zagreb provides an interesting lesson to modern innovators, as we are often faced with the same dilemma as the Zagreb City Hall faced when they encountered Tesla’s proposal in 1892. The city had made substantial investments in a gas network, as well as the lamps tied to it, and considered their solution to be quite advanced at the time. In 1863, Zagreb supported 364 gas lanterns in their city, providing illumination to their citizens (the lamps were also lit by hand each night, thus providing jobs as well). Even today, Zagreb still has 214 gas lamps in operation in the old town area.

When faced with Tesla’s proposal for electric power, the members of City Hall likely saw their existing innovation as something that worked well and that had required a large investment, as opposed to an unproven technology. As innovators we sometimes face both sides of this dilemma. Sometimes we find ourselves in the role of Tesla, trying to convince a group of entrenched decisionmakers of the superiority of a new approach. When those decisionmakers have made significant investments in what they considered an innovative solution, our challenge is even greater. Yet sometimes we may find ourselves in the role of the City Hall, faced with the decision as to whether to scrap a large investment in a previous innovation in exchange for the promise of something that could be much better.

For the modern innovator, I would propose the “Tesla Zagreb Dilemma†as a way to think about both scenarios. If we are proposing our innovation against an entrenched competitor, we may need to invest more time than we previously thought in finding ways to prove our new technology is better than the existing one. If we are considering an innovation to replace an existing investment, we need to spend more time truly considering the benefits of the new technology and not allow the size of our previous investment to prevent us from making a truly innovative improvement in technology.

Guild Signs (“Cimeriâ€), Building Tiles, and Ties

Ironmonger’s Guild Sign

Varazdin is a small and charming city in Northern Croatia which served as the country’s capital in 1756 until it was destroyed by fire. The town is better known today as a popular tourist destination with an interesting and protected old town area with pedestrian-only zones and cafes in spacious plazas. One thing that stands out in Varazdin are the presence of small carved or cast objects on certain streets. These objects, known as Guild Signs or “Cimeri,†from the word “cimer†which means “trade,†were required to be hung above the shops of craftsmen to show their membership in the guild. These show the type of work that takes place in that shop, such as an ironmonger, represented by a small suit of armor displayed above a shop in King Tomislav Square. Others in Varazdin include the Siren for overseas importers (also in King Tomislav Square), the turtle for grocers (on Ivan Gundulic Street), and the horseshoe for blacksmiths (on Ivan Padovec Street). In addition to providing an easy way to make sure people operating shops are members of the appropriate guild (and thus limit competition), the symbols also advertised services to those who were illiterate and could not read a written sign (more of a problem centuries ago than it is today).

Tile Manufacturer’s Building

In the Croatian capital city of Zagreb, a similar phenomenon exists but more in terms of the advertising benefits of physical symbols. A surprising number of buildings in Zagreb are yellow, which was the most fashionable and prestigious color for the Austro-Hungarian Empire in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. One particularly stunning house in Zagreb has yellow and blue tiles on its façade and stands out among the many fascinating buildings in the city. This house was owned by a manufacturer of colorful building tiles and the owner decided that the best way to advertise his wares was to put them on his own home on Gunduliceva Street in Zagreb. It would be difficult to walk past this house without wondering how the owner was able to create such an architectural masterpiece, which is precisely the reason why he chose to use his own company’s tiles in decorating the home.

Croatian Soldiers with Red Tie (Cravat)

In addition to the guild signs and yellow buildings, another interesting symbol in Croatia is something of which the local residents are quite proud – the red necktie. Indeed, much to the consternation of people forced to wear business attire around the world today, the source of the necktie is the country of Croatia. During the early 1800s, as the French Emperor Napoleon was leading his troops in conflict across Europe, the French needed to augment their troops with mercenaries. One group that Napoleon hired was from Croatia and those troops earned plaudits from the Emperor because of their ferocity in fighting. These troops also stood out because they wore red scarves tied around their necks. The French heard that these troops were Croats, which eventually evolved into the word “cravat,†which is French for necktie. Over time, the symbol of the fighting Croats became a symbol of fashion.

Innovation Thoughts – After seeing these various means of physically showing the type of work performed in the ironmonger’s shop, the tile manufacturer’s home, or the red necktie, I began to think about the symbols that we as innovators could use to advertise our wares. In my former workplace a popular sign would prominently show the word “THINK†as a way of spurring innovation. Another idea would be to have models of prominent innovations of the past, such as da Vinci’s prototypes, a Watt steam engine, or any famous modern invention. In the current era, a photo of a black turtleneck-clad Steve Jobs would speak volumes about one’s thoughts on innovation, even if that example is probably over-used. An interesting physical symbol that represents work in a clever way is a single piece of currency with the value of 100 trillion Zimbabwe dollars that Economic Professors like to keep on hand in their office to show students what hyperinflation can mean.

A simple symbol can say a lot about what one does, especially when it forces the viewer to think more intensively about the topic. It may be worthwhile for an innovator to spend a little time thinking about how he or she would want to represent visually the work one has underway on a specific innovation initiative, taking advantage of the fact that humans can process and absorb images more rapidly than a paragraph of complex sentences about a project. Boiling a project down to its core elements may also be useful in forcing one to really think about what one is trying to accomplish in the innovation project.

The Orient Express Hotel

Hotel Esplanade in Zagreb

When one stays at the Hotel Esplanade in Zagreb, the first thing one notices are a series of clocks and mail slots in the lobby that harken back to a bygone era in travel. The clocks show the time in major European capitals, while the mail slots suggest that hotel residents may have a need to pick up correspondence as part of the journey. The hotel, built in 1925, is situated directly next to the central train station in Zagreb, as opposed to other luxury hotels that are located near major public squares or parks closer to the city center. The reason this hotel occupies such as location is because it was one of the original Orient Express hotels.

The Orient Express is perhaps the most famous luxury train in the world. Launched in 1883 to connect the cities of Paris and Istanbul (with many stops in between), the Orient Express is synonymous with luxury train travel. Yet the Orient Express was more than a train. It encompassed an entire hospitality system, including hotels in key cities along the way. These hotels had to evince the same style and sophistication as the Orient Express trains themselves, so that a passenger moving from a room on the train to a room in the hotel would enjoy similar levels of luxury throughout the experience.

Innovation Thoughts – Patrick Rondeau and B.J. Bhatt of Butler University write of the concept of synthetic innovation, which they define as combining “existing technologies and ideas in new and never previously done ways to create significantly new products.â€Â Of particular interest to the innovator are cases where the combination of two components results in a solution that far surpasses the sum of the value of the individual components. The combination of the Orient Express trains and the ecosystem of luxury hotels created an offering that far surpassed the individual components of the solution. A traveler taking advantage of this combined solution would be assured of staying in appropriately luxurious surroundings whether he or she was engaged in the mobile or stationary portion of his or her trip. The traveler would not be dependent on the train schedule to find luxurious dwellings in a location and could seamlessly move from one location to another without sacrificing any part of the experience. The ability to receive correspondence at fixed locations along the route also enhanced the overall service. For the modern innovator, the lesson here is to think about entire ecosystems when designing innovative solutions, rather than just focusing intensively only a single component. By expanding the scope of the offering, the innovator can create an overall solution that is greater than the sum of its individual parts.

The Zagreb Skyscraper

Zagreb Skyscraper in Ban Jelacic Square

Ban Jelacic Square is the central hub of Zagreb. The square is a popular meeting-place for locals, a key hub in the streetcar transportation network, home to various street markets, as well as the statue of the eponymous Josip Jelacic, a General who led Croats in the revolutions of 1848 and who abolished serfdom in Croatia. As one looks around the square, one sees the well-preserved facades of 19th and early 20th century buildings, rivaling the beauty of any of the famed cities of Europe. Unfortunately, before one can complete a full panorama view of the square, one sees a building that clearly does not fit with the historical motif. The building is the 16-story Zagreb Skyscraper, built in 1959 during the Tito Era in Yugoslavia (after Marshall Tito, the strongman who ran the country throughout the Communist Era). At the time it was the tallest building in all of Yugoslavia and was the first external steel-framed building in the country.

Other Side of Ban Jelacic Square

Innovation Thoughts – The Zagreb Skyscraper was certainly innovative at the time of its construction, demonstrating construction techniques and reaching heights that were non-existent elsewhere in the country. Although the building serves as a platform for an observation deck that overlooks the city as well as much-needed office space, this innovation 59 years later looks to be something that perhaps should not have been built. For innovators, the lesson here is that just because one has the technology and capability to build something, that does not mean that one should build it. One should be aware of other externalities and considerations before launching into a transformative project. In other words, the location in which an innovation will be inserted can be as important as the novelty of the innovation itself. Applying an innovation in the wrong environment diminishes the value of the innovation. Interestingly, many residents would like to see the Skyscraper go and replace it with a building that fits the historical motif with the rest of the square. However, the skyscraper does have historical merit as the first of its kind in the country, so no consensus exists on what to do with the building.

Â

Gregory of Nin and Ivan Mestrovic

Gregory of Nin Statue in Split

One of the most famous Croatian artists is the sculptor Ivan Mestrovic. Born to a peasant family in the Slavonia region of Croatia in 1883, Mestrovic served as the apprentice to a marble cutter at the young age of 13 and went on to study at the Vienna Academy, receiving acclaim for a brief stint in Paris from the renowned sculptor Auguste Rodin. Mestrovic went on to work and teach in the United States, and his works appear around the world, including Chicago, Syracuse, and throughout the former Yugoslavia.

The statues that Croatians prize most among the works that Mestrovic created are those of Bishop Gregory of Nin, which appear in the cities of Varazdin, Split, and Nin. Bishop Gregory translated the Christian liturgy into the Croatian language in 926, thus allowing the illiterate peasants of the country to understand Church services, which had previously only been provided in Latin. Gregory is viewed as a key figure in preserving the Croatian language and thus its culture, and his statues are well-loved by the locals (including the legend of rubbing his big toe for good luck). The statues all have a peculiar characteristic, however, beyond the shiny bronze toe. The face of Gregory of Nin is definitely not that of the actual Bishop Gregory. In fact, no one knows what Gregory’s face should look like, since no images of Gregory exist. The face on the statue is that of the sculptor Mestrovic. Indeed, one can see an uncanny resemblance between old photos of the artist and the sculpture of Gregory.

Gregory of Nin Statue in Varazdin

Innovation Thoughts – Mestrovic was faced with a seemingly impossible task when he landed the commission to create sculptures of Gregory. Since no image existed of Gregory’s face, Mestrovic chose a tool available to anyone faced with uncertainty – rely on what is most familiar to you – yourself. Rather than trying to invent a face from scratch or taking the face from another image, Mestrovic made a self-portrait for the statue’s face. This ensured that the face with have details and would also serve as an additional signature by the sculptor on his work. The same phenomenon appears in the Croatian coastal city of Trogir, where the sculptor Radovan inserted his won face into some of the figures he carved in stone in the entry portal into the Cathedral of St Lawrence. Mestrovic also did this in Trogir for a sculpture of St. John. For the innovator, this serves as a reminder that when one faces a situation of great uncertainty, the best approach may be to resort to an approach with which one is most familiar. One can rely on one’s own experience and insights to solve challenges.

Zagreb Art Pavilion

Zagreb Art Pavilion

In a city of beautiful late 19th and early 20th century buildings, the Zagreb Art Pavilion at the northern end of King Tomislav Square stands out as a particularly intriguing structure. What is interesting is that the building was not originally constructed at this location. Rather, it was put together in Budapest in 1896 to house the Croatian Pavilion at the Budapest Millennial Exhibition. After the exhibition ended, the building was taken apart and shipped by train to Zagreb, then rebuilt at its present location. Today, the building hosts art shows and other cultural events and remains a fixture of the Zagreb architectural scene.

Innovation Thoughts – In today’s era where conservation is important, the innovator has a unique challenge to find ways to recycle and reuse precious resources. The best way to conserve resources is to think about the lifecycle of a product when one is creating it, so the innovator should spend time upfront thinking about the long-term use if one’s innovation. Had the builders of the Zagreb Pavilion in Budapest only focused on the duration of the 1896 show, their amazing construction would have likely been taken down and reverted to scrap. Instead, they chose to design and build their structure in a way where it could be disassembled and transported back to Zagreb so that it would fulfill a useful life after the show. The Croatia pavilion was likely not the most architecturally stunning building in the Budapest Expo, but its novelty was in the versatility of its design in addition to the basic beauty of the structure. My guess is they would have been quite pleased to hear that 122 years later their structure is still intact and serving a useful purpose for the people of Croatia.

Â

The Zagreb Cathedral

Zagreb Cathedral

Although Zagreb ranks in the middle tier among the cities in Europe with great cathedrals, the Zagreb Cathedral is nonetheless an impressive ecclesiastical building. Its size is quite large (in terms of the 105-meter height of its bell towers), and it shows a blend of different architectural styles, representing the different Romanesque and Gothic influences of French, German, and Czech schools of design over the centuries. The cathedral dates to the reign of King Ladislaus in 1040 and has been rebuilt several times over its lifetime, with a major construction effort undertaken in the 13th century by King Andrew II.

The most interesting renovation work, however, occurred in 1880 after much of the structure was destroyed in a major earthquake that rattled Zagreb. For this effort, the renovators made a decision to use a different kind of stone than was used in the original cathedral. The new stone came from two quarries that were geographically closer to Zagreb and thus cheaper and easier to obtain. The stone had the same appearance as the original stone, so the renovators assumed that the new stone would be an optimal means of rebuilding the cathedral. Unfortunately, the new stone proved to be of poor quality and was unable to withstand the weather extremes and pollution in the Zagreb area, which led some parts of the church to appear as though they were melting, rendering stone sculptures unrecognizable. The builders stopped using the new stone and began a revised restoration program in 1968 in which they used the stone from the original quarry for the cathedral. Work continues to this day on the building, as pieces of the new stone are replaced gradually with more durable stone from the original quarry.

Poor Quality Stone on Left; Original Stone on Right

Innovation Thoughts – One mantra of innovation work is efficiency. When faced with a challenge, such as transforming a business process or finding a new way of operating, we place a high degree of importance of the core efficiency of our proposed solution. Presumably, if a transformed process produces the same amount of output (or more) than the original process and does so with fewer inputs, then that new process is deemed more efficient and thus superior to the old. In the case of the Zagreb Cathedral, the team that set about rebuilding the structure after the 1880 earthquake took this lesson to heart in selecting stone from closer quarries, assuming that they would be able to get more work done with fewer resources and speed the rebuilding of the church at a lower cost. It is difficult to blame them for making such an assumption, especially in an environment in which much of the city was destroyed and resources were limited across the board for reconstruction.

Yet the end result of their work, which is a deteriorating façade that requires replacement of all the lower-quality stone, shows the potential perils of this efficiency-focused approach. For the modern innovator, one should periodically double check one’s assumptions about a new process to make sure that the efficiency that one is counting on delivering is truly taking into consideration all the potential costs and externalities associated with the possible improvement. Had the renovators of the cathedral performed a side-by-side test of the new rock before using it in large quantities, they might have been able to see its weakness compared to the old stone, which certainly would outweigh any savings to be derived from the lower material and transportation costs of the new quarries.

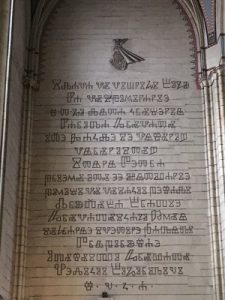

Glagolotic Script

Glagolitic Script in Zagreb Cathedral

In Croatia, one periodically sees a strange-looking set of characters which appear to be a form of writing but bear little resemblance to anything we are accustomed to seeing in the modern world. This script is the oldest known Slavic alphabet and was invented in the 9th century by the Byzantine Monk Saint Cyril. In the year 863, the Byzantine Emperor Michael III sent Saint Cyril and his brother, Saint Methodius, to the Slavic regions to spread Christianity among the Slavs. Since the Slavs could not speak or recognize the Latin or Greek alphabets, the brothers concluded that they needed to find a way to translate the Christian teachings into the Old Slavic language in a way that the Slavs could understand. Because the Old Slavic language proved impossible to transcribe using the existing Latin or Greek alphabets, Cyril and Methodius concluded that they needed to create an entirely new script, which they called the Glagolitic script. The new script was taught to a set of students and propagated in Western and Southern Slavic areas and endured until the 19th century (used by the Croatian Church to write what was known as the Church Slavonic), but eventually died out and was replaced by the Latin alphabet.

Innovation Thoughts – The case of the Glagolitic Script could serve as an inspirational tale for innovators seeking to create something entirely new. After all, the work of just two lone monks in the Slavic lands resulted in the creation of an entirely new alphabet that survived 1,000 years (and still exists today even though it is not in wide usage). Indeed, the work of Cyril and Methodius is an impressive application of a new idea (the new script) to solve an existing problem (how to communicate the liturgy to people whose language could not be transcribed using the Greek or Latin alphabets). Yet the fact that Glagolitic script ultimately died out and even during its lifetime was only of limited use, suggests that it is also possible to take an alternative view of the monks’ endeavor.

Although it is impossible to know all of the environmental factors that drove the monks to create this script, one has to wonder whether the time and energy they focused on creating, teaching, and disseminating the new script could have been better spent on redoubling their efforts to find a way to make the Latin alphabet work for the Old Slavic language. Sometimes an innovator needs to step back from a problem and recalibrate one’s efforts. It is possible to follow a new line of thinking down a proverbial rabbit hole in which one new idea begets another new idea and, before too long, one has reached what we would now (interestingly) term a Byzantine solution, or a solution that is overly, and unnecessarily, complicated. Sometimes it makes sense for the innovator to step away from complexity and start over from a simpler foundation.

Â

Bloody Bridge

Bloody Bridge Street

Along the lines of Voltaire’s statement that the Holy Roman Empire was in no way Holy, nor Roman, nor an Empire, there is a famous street in Zagreb called Bloody Bridge (Krvavi Most) that today is neither Bloody nor a Bridge. The road attained its name from a period in the 14th and 15th centuries when it represented the dividing line between the two towns (Gradec and Captol) that united in the 18th century to form what we know today as Zagreb. Beneath the bridge ran the Mandusevac creek, which was later paved over and disappeared completely. Prior to unification, the two towns were frequently at war with each other for political and economic reasons, and the Bloody Bridge was the site where these altercations frequently occurred.

Innovation Thoughts – The Bloody Bridge provides the innovator with a glimpse into an alternative technique for salvaging new ideas from old concepts. Modern residents of Zagreb are not proud of the recurring conflict that took place at the Bloody Bridge, but when reminiscing about this site they try to focus on one positive aspect of the site. In one instance in the 1500s, the Bishop of Kaptol excommunicated the entire town of Gradec, which led to violent attacks by the residents of Gradec against the city of Kaptol. Rather than focusing on this bloodletting, scholars of Zagreb used the information documented by the Bishop to establish a precise census of the population of Gradec in the 1500s, since the Bishop chose to write down the names of every resident of Gradec as part of the excommunication. This helped improve our understanding of the size of the city at the time and increased our overall sense of how the city evolved over the centuries. For the modern innovator, it is important to think about all the different ways one can obtain information when trying to solve a puzzle, especially those methods that may not, at first, seem promising.

Slovenia

Just north of Croatia is the lesser-known country of Slovenia, not to be confused with the Croatian region of Slavonia. Slovenians like to say that their everything is close to their country. The country sits at a crossroads of several nations, bordering Italy, Austria, Hungary, and Croatia. During the Yugoslavian era, Slovenia was the most prosperous of the republics, with the highest Gross Domestic Product per capita of any of the Yugoslavian Republics. Although it was the smallest in physical size, its economic prowess and proximity to Italy and Austria gave it more of a European perspective than the other republics. After Tito’s death, Slovenia was the first Yugoslav Republic to declare independence in June 1991 and has achieved several other “firsts,†by joining the EU and NATO in 2004 and switching to the Euro currency in 2007. Indeed, when one spends time in Slovenia one feels more like a resident of Austria than of the former Yugoslavia. Slovenia’s crown jewel is its highly walkable and architecturally-stunning capital city of Ljubljana.

Joze Plecnik

It is impossible to walk the streets of Ljubljana without feeling the presence of the great Slovenian architect Joze Plecnik. Born in Ljubljana in 1872, Plecnik left home at the age of 16 to study as a furniture designer at the School of Industry and Crafts in Graz, Austria. He moved on in 1895 to the Vienna Art Academy and studied architecture with the Austrian architect Otto Wagner. At the behest of Czechoslovak President Tomas Masaryk, Plecnik spent the years 1911-1920 working in Prague on a series of projects at the Prague Castle as well as the Church of the Most Sacred Heart of Our Lord in Podebrad Square. Plecnik returned to the town of his birth in 1921 with an appointment as a founding faculty member at the Ljubljana School of Architecture and set about transforming Ljubljana into what he envisioned as the “new Athens,†modeling his work to include the Greek columns and other architectural attributes of the Greek capital city. Plecnik believed in the architectural maxim of “architecturae perennis,†which translates into eternal architecture. He thought that the role of the architect was to build not just for the present, but to take into consideration future uses as well.

The Triple Bridge (Tromostovje)

Triple Bridge – Ljubljana

Situated at the center of the old town pedestrian-only zone in Ljubljana, the Triple Bridge is one of Joze Plecnik’s most famous works. The bridge is not a massive structure like the iconic bridges of other cities (such as the Brooklyn Bridge or the Golden Gate Bridge), but it holds a similar sway over the minds of the city’s residents nonetheless. A single bridge has existed at this spot crossing the Ljubljanica River as far back as 1280, and the edifice has undergone a series of modifications and renovations throughout the centuries.  In its last iteration, it was known as the Franciscan Bridge, which was built in 1842 and consisted of two stone arches with metal fences on the sides. Plecnik’s work on the bridge started in 1929 when he decided to renovate the original single stone bridge and add two footbridges alongside it running at slight angles to the original bridge. The side bridges were meant for pedestrian traffic, as Plecnik observed that the single span of the original bridge was crowded with automobile traffic and pedestrians trying to navigate a single thoroughfare. This need for car traffic was removed in 2007 when the entire area became part of a pedestrian zone. The bridge itself is simple and elegant in its design and proves highly functional in terms of aiding traffic flow in this busy area.

Had Plecnik only added the two converging side pedestrian bridges during his renovation in 1929, his accomplishment would have been a great one and would continue to be an iconic symbol of the city of Ljubljana. Yet Plecnik also applied his stamp to the bridge in the form of designing it holistically and thinking about how it fit into the overall urban environment of his hometown. In addition to coming up with the idea of adding the two additional spans, he also thought about how the bridge would be integrated into the rest of the city in both aesthetic and practical ways. He designed balusters for the bridge that matched balusters he placed on other structures in the city. He designed new lampposts for the bridge that reflected the style of the balusters and fit in with the motif of the bridge. He also added things to the bridge that were not traditionally thought of as integral to bridge design – trash cans that matched his design motif and free public restrooms hidden underneath the spans of the bridge. Anyone who has spent a lot of time walking in great cities of the world has lamented the lack of easily accessible public toilet facilities. Plecnik knew that his bridge was more than a structure to move people from one side of a river to the other – it was part of the overall urban landscape. To this day, the restrooms he designed are free and clean and improve the livability of the central part of Ljubljana.

Innovation Thoughts – As innovators we sometimes struggle to find a single solution to a problem that, in an of itself, would strike others as “brilliant.â€Â We want to find innovations that leap ahead of current technological approaches, resulting in a huge gap between an existing product or process and our new solution. Sometimes we are able to make this leap and are lauded for it, but most of the time this proves exceedingly difficult to do and we need to find ways to take small improvements and make them even better. Plecnik’s approach to urban design provides us with an example of how to do this. Plecnik viewed his architectural creations in the context of how they operated within the city and how they aligned with the overall aesthetics and operations of the urban area. In his commission for the Triple Bridge, he could have designed a large, visually striking bridge that stood out in the city and made everyone envious of his creativity in design. Yet he chose a more functional design that was visually integrated with the rest of the city and highly functional (bathrooms and extra pathways for pedestrians).

Venice Pedestrian Bridge

This highly functional design by Plecnik contrasts sharply with a new pedestrian bridge in Venice that connects the railway station to the Piazzale Roma (the car, bus, and ferry terminal for Venice). The 94-meter long Constitution Bridge, designed by the Spanish Architect Santiago Calatrava, is architecturally stunning with a large sweeping arch and irregularly spaced glass steps. Yet it lacks some of the core functionality one would expect from such a bridge. Connecting key transportation hubs, one would expect a flat lane on the side to accommodate travelers using rolling suitcases. This is not offered on the bridge, which consists only of steps. The steps are also irregularly spaced, which has led to pedestrian accidents as tourists, who are paying attention to the beauty of Venice and not their feet, have fallen while traversing the bridge. The bridge’s glass floor can also be slippery when it rains, which is something that happens frequently in Venice. The same lack of logistical functionality can be seen in Calatrava’s Oculus Terminal in New York City, where it is difficult to move from some levels to others in the great atrium. Plecnik’s designs may lack the sweeping and stunning forms of Calatrava, but they more than make up for it in terms of utility. Innovation should be as much about function as it is about form.

Ljubljana Central Market Colonnade

Ljubljana Central Market

Another major work by Plecnik that combines beauty and function is the Ljubljana Central Market Colonnade. Residents of Ljubljana have frequented a market in the central old town area for hundreds of years, but in 1940, Plecnik set out to design a new building that would trace effortlessly along the river and provide a series of functional spaces for the various market participants to offer their wares. He designed a two-story structure with a long, sweeping series of columns that followed the river from the Triple Bridge to the Dragon Bridge. The market has space for flower vendors, indoor (hygienic) and separate areas for meat, dairy, spice, and fish vendors, as well as outdoor covered areas for fruits, vegetables, and arts and crafts. The design of the structure is at once utilitarian, in terms of how well it organizes the various spaces for market vendors, and also visually striking. Yet the structure maintains what one could refer to as a human scale. One technique that Plecnik uses to accomplish this is by leveraging slightly decreasing column sizes so as one looks down the colonnade of the market, the structure seems to fade gracefully into the distance rather than overwhelming the visitor.

Ljubljana Central Market

Innovation Thoughts – Plecnik’s Central Market design reminds us that functional solutions can also be beautiful, and that the two categories are not always mutually exclusive. Perhaps his human centered design was a function of his formative years spent as a furniture designer, thinking about things at a human scale. Furniture design requires the artist to think at the level of a single human being, in terms of how that person would use the furniture. Experiences in the formative years for an architect can certainly be deterministic for that architect’s future works. In a recent interview with the famous modern architect Renzo Piano, Alexandra Wolfe noted that Renzo Piano as a child “would accompany his father [who worked in the construction industry] to building sites and watch sand and stones become the foundation for steel and planks of wood and then, finally, entire structures.â€Â Piano said that he grew up “with this idea that this is giving shape, creating shelter.â€Â His modern structures reflect this thought pattern, with a focus on sheltering structures.

Altar in Holy Trinity Church

Plecnik’s larger architectural works, conversely, reflect an attention to detail at the individual human level. At the nearby Church of the Holy Trinity in central Ljubljana, Plecnik designed not just the exterior structure of the church but also designed the altar used in the church, wanting make sure that every element of the church worked in unison to accomplish the goals of the structure. Since so much of the time spent by people in the church would be focused on events at the altar, Plecnik knew that its design was as important as the design of the stained windows and arches. For the innovator, the lesson here is that an attention to detail, even to seemingly less-consequential components, can lead to an overall solution that is quite innovative.

Slovene National and University Library

National and University Library Facade

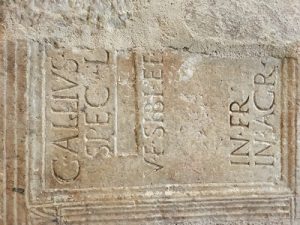

Roman Stone in St Donatus Church in Zadar

Another of Plecnik’s most beloved works is the Slovene National and University Library in Ljubljana, built between 1936 and 1941. The building reflects design influences of an Italian Palazzo but with unique flourishes from Plecnik, such as the juxtaposition of stone walls with delicate glass. The two most interesting design elements, however, are much more significant and reflect Plecnik’s desire to create “architecturae perennis,†or everlasting architecture. The stone façade of the building is made of both new and old stone pieces. The older stone pieces were salvaged from damaged buildings in the area, harkening back to a style of construction that is as old as the ages, as societies for millennia have used stone from older buildings to ease the construction of their newer buildings. A great example of this is the Church of St. Donatus in Zadar, Croatia, which is a pre-Romanesque Basilica that was constructed using bricks from the old Roman city in the area. As one walks around the interior of the church, one can see Latin script and Roman carvings on some of the bricks in the foundation of the basilica, clearly showing how the original builders used nearby materials for their structure. Plecnik cleverly mimics this approach by using old stones in the external façade of his structure for the library, reflecting back on a timeless technique for construction.

Entrance to National and University Library

A second method used by Plecnik to tie the Slovene National and University Library to the past appears in the entrance hallway to the building. As one enters, the hallway is dark and one must proceed towards the light in the center of the library. The hallway itself has tall, dark stone columns that mimic the style of entranceways to Egyptian Pharaonic tombs but, instead of going down towards darkness as in a tomb, in the library one walks up towards the light of wisdom. In this section of the building, Plecnik is paying tribute to the timeless structures of the Egyptians and the constant thirst for knowledge that is a key attribute of the human experience.

Innovation Thoughts – One of the greatest achievements one can accomplish as an innovator is to create a clever solution that solves a current business problem, such as an improvement to a process or a new product or service that succeeds in the marketplace. Yet there is another objective that innovation practitioners should consider in their work efforts – the goal of timelessness. This kind of innovation harkens to great achievements of the past while solving modern challenges. This is a particularly difficult type of innovation to achieve, but it can be among the most fulfilling when it does succeed.

Sources:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Balkans

https://www.likealocalguide.com/zagreb/tesla-cabinet

https://tehnicki-muzej.hr/en/permanent-exhibition/

https://www.infozagreb.hr/news/gas-lantern-i-love-you-so-54abf82134547

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Varazdin

https://www.tourism-varazdin.hr/en/day-in-varazdin/the-guild-signs-cimeri/

Mahala Ruddell, “803 Norfolk and Quarantine in Park City,†The Park Record (June 20, 2018), p. A11.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Orient_Express

https://www.infozagreb.hr/explore-zagreb/attractions/squares/king-tomislav-square

Rondeau, Patrick and Bhatt, B. J., “A framework for assessing product innovation strategies in a competitive context” (1994) Scholarship and Professional Work – Business. 43.

https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/cob_papers/43

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Josip_Jelacic

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Ivan-Mestrovic

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gregory_of_Nin

https://www.infozagreb.hr/explore-zagreb/attractions/architectural-monuments/-54abf7ebee483

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Art_Pavilion,_Zagreb

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Glagolitic_script

https://croatianattractions.com/bloody-bridge-the-street-in-zagreb/

https://www.croatiatraveller.com/Zagreb_region/History.htm

https://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/Voltaire

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Krvavi_Most

https://chnm.gmu.edu/1989/items/show/671

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Slovenia

https://www.visitljubljana.com/en/visitors/things-to-do/sightseeing/article/plecniks-ljubljana/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joze_Plecnik

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ljubljana_Central_Market

https://www.visitljubljana.com/en/visitors/things-to-do/sightseeing/cobblers-bridge/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cobblers’_Bridge

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Triple_Bridge

Alexandra Wolfe, “Renzo Piano: Airy, Open Structures for Elite Institutions,†The Wall Street Journal (June 23, 2018), C6.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/National_and_University_Library_of_Slovenia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Church_of_St._Donatus

Photos courtesy of the author except as follows:

Croat Regiment and Tie (Cravat) provided by Roberta F. [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], from Wikimedia Commons

Zagreb Art Pavilion Photo by Diego Delso, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=32424940

Wait! Before you go…

Choose how you want the latest innovation content delivered to you:

- Daily — RSS Feed — Email — Twitter — Facebook — Linkedin Today

- Weekly — Email Newsletter — Free Magazine — Linkedin Group

Scott Bowden is founder and CEO of Bridgeton West, LLC, a firm consultancy focusing on historical innovation. Scott previously worked for IBM Global Services and the Independent Research and Information Services Corporation. Scott has a PhD in Government/International Relations from Georgetown University.

Scott Bowden is founder and CEO of Bridgeton West, LLC, a firm consultancy focusing on historical innovation. Scott previously worked for IBM Global Services and the Independent Research and Information Services Corporation. Scott has a PhD in Government/International Relations from Georgetown University.

NEVER MISS ANOTHER NEWSLETTER!

LATEST BLOGS

How To Stay Connected to Your Co-Workers as a Digital Nomad

The digital nomad lifestyle has grown dramatically in recent years. The number of digital nomads has increased by 42%…

Read MoreCarbon neutrality: what is it, how to achieve it and why you should care

When sustainability is on the agenda, you’re likely to hear many terms mentioned that you may or may not be…

Read More