Eliminate the seven wastes of innovation to create flow.

“Lean is a way to do more and more with less and less — less human effort, less equipment, less time, and less space — while coming closer and closer to providing customers exactly what they want.†– Womack and Jones, 1996, (Source)

During the late 1980s, an MIT research team coined the term “leanâ€Â to describe Toyota’s manufacturing business. The idea of lean methodology, however, started way back with Ford’s first assembly line. Toyota executives simply took Ford’s process flow, provided a wide variety of product offerings, and refined it into what is today known as the Toyota Production System.

“…Lean Thinkers need a vision before picking up our lean tools…thinking deeply about purpose, process, people is the key to doing this.â€

— Womack (Source)

With lean’s continued success, more and more companies are starting to adopt lean methodologies in their workplaces. Companies like GE and Motorola are seen as masters at using these approaches to streamline and scale their manufacturing processes by reducing waste.

However, organizations are now aware that they must also continually innovate to stay relevant. Organizations have been trying to bring innovation in-house and scale that capability for over a decade. It is more challenging for a legacy organization to try to marry innovation performance with operational efficiency to bring down the transactional cost of being consistently innovative. Scaling innovation is a dire need of the day.

In this article, I argue that in-house innovation is much like in-house manufacturing. Take for example, in the article below, the author describes how lean can lead to a new workplace with a people-centric approach, providing employees autonomy, a sense of belonging, instilling mutual respect, promoting team play/collaboration, and taking a bottom-up approach to culture change.

I argue that just as manufacturing went through a transformation in the 1990s, so must innovation today. Innovation architects have a lot to learn from lean manufacturing methods. By studying how lean manufacturing brought change to a new paradigm shift to scale, bringing efficiency, and creating a great workplace environment for employees, we can do the same for innovation.

MANUFACTURING is about managing FLOW of raw materials to mass-produce and customize products.

INNOVATION is about managing FLOW of ideas to create a robust new offering.

For this discussion, let’s focus on the concept of waste removal in lean manufacturing, also known as Muda (a Japanese word meaning uselessness or wastefulness), and apply it to innovation. In this next table, I compare the seven manufacturing waste as listed in Muda to the seven wastes in innovation in the modern workplace. Astute readers will notice the many similarities between the two methodologies.

Let’s look at why these waste happens in an organization and what strategies one might adopt to reduce such waste.

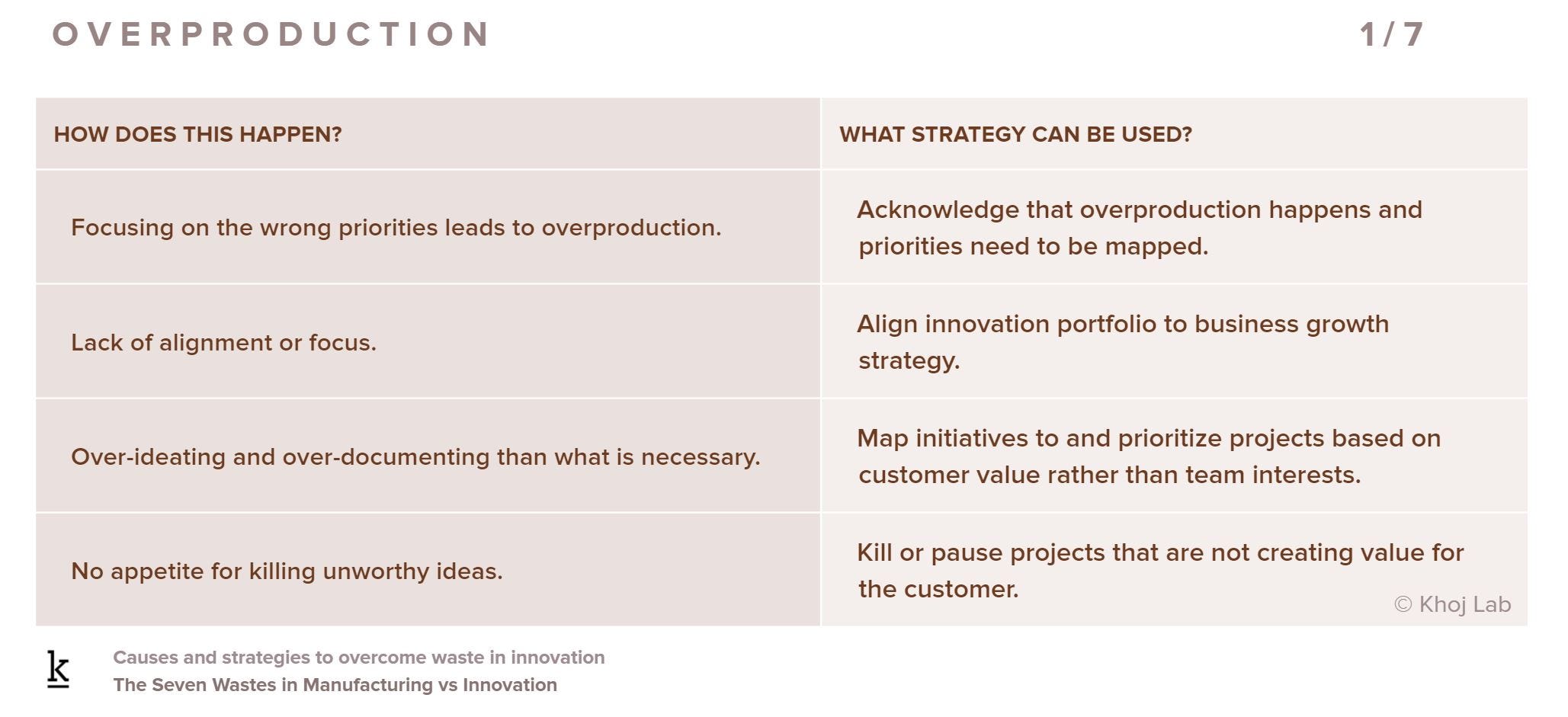

- Overproduction

In manufacturing, overproduction is about producing products beyond what the customer has ordered.

In innovation, overproduction of ideas adds little value to the customer or the business.

2. Excess Inventory

In manufacturing, excess inventory refers to the work in progress (WIP) — excess stock of finished goods and raw materials that a company holds.

In innovation, excess inventory also refers to the work in progress (WIP) — excess stock of ideas, unused/underutilized research reports, materials, samples, and prototypes.

3. Waiting

In manufacturing, waiting is the act of waiting for a machine to finish, for a product to arrive, or any other cause.

In innovation, waiting is the delay created due to lack of inputs, peer reviews, funding decisions, approvals arising due to bureaucracy, inspections, feedback/approval mechanisms.

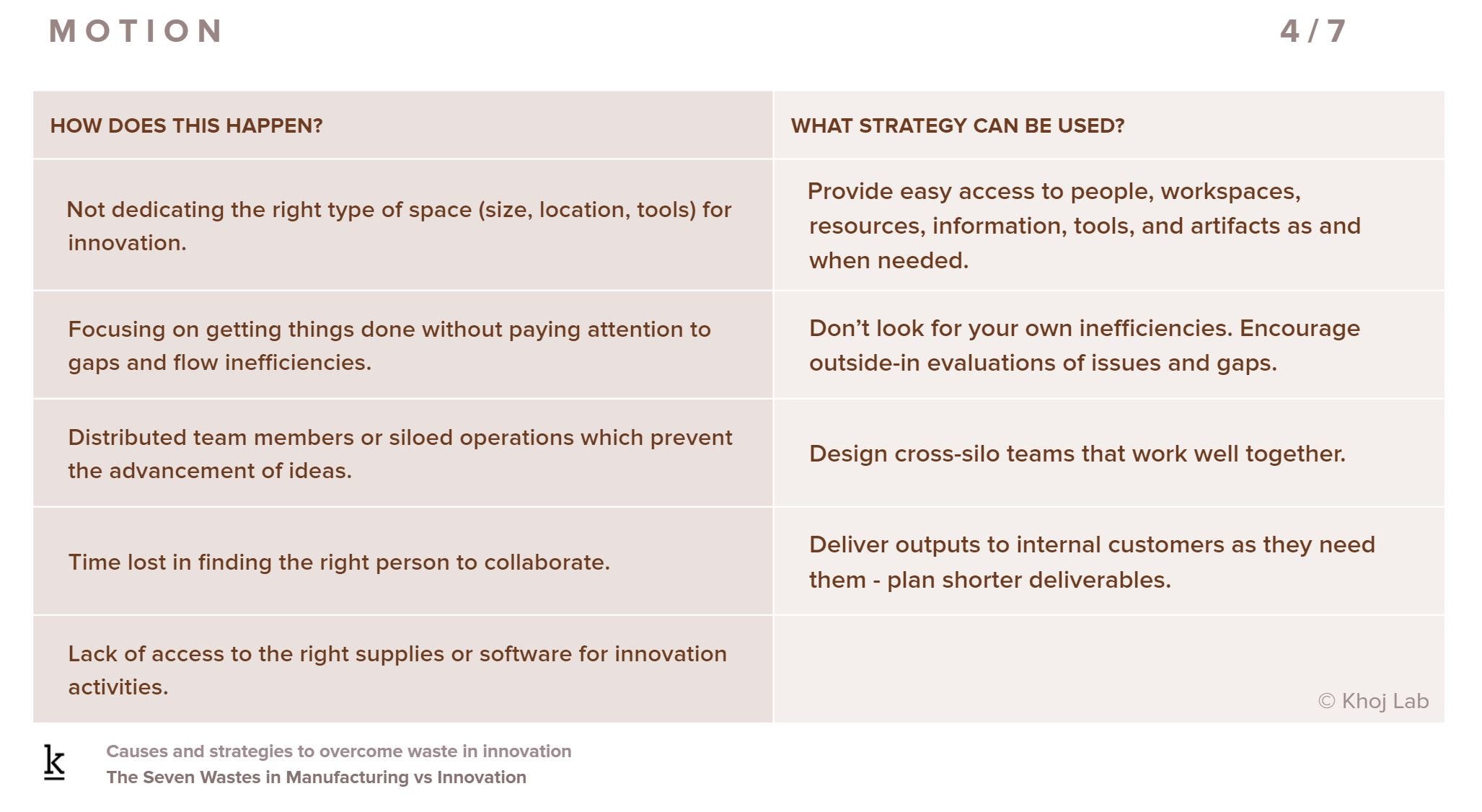

4. Motion

In manufacturing, motion refers to the physical movement of a person or machine while conducting an operation.

In innovation, motion refers to a person’s physical movement needed to access whiteboards, labs, or stored prototypes during an experiment or exploration cycle.

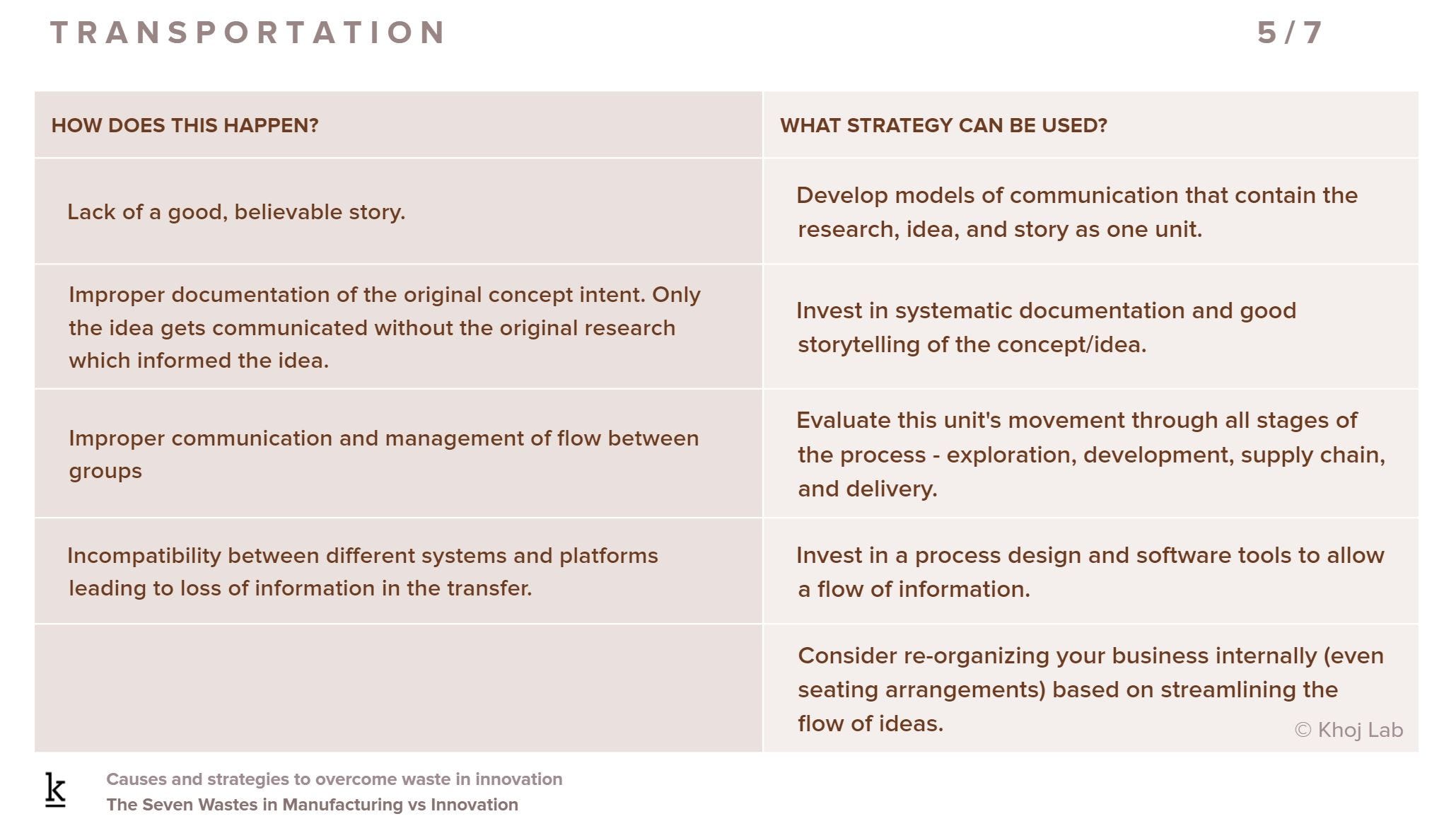

5. Transportation

In manufacturing, transportation is the movement of products between operations and locations. It can involve raw components, sub-assemblies, empty boxes, or just about anything required for production. Transporting material is a necessary activity, but it doesn’t add value to the end product.

In innovation, transportation is the movement of the concept or idea between disciplines or groups or from one stage to the next. While it does not add value to the end product, it is critical for the organization’s stakeholder buy-in.

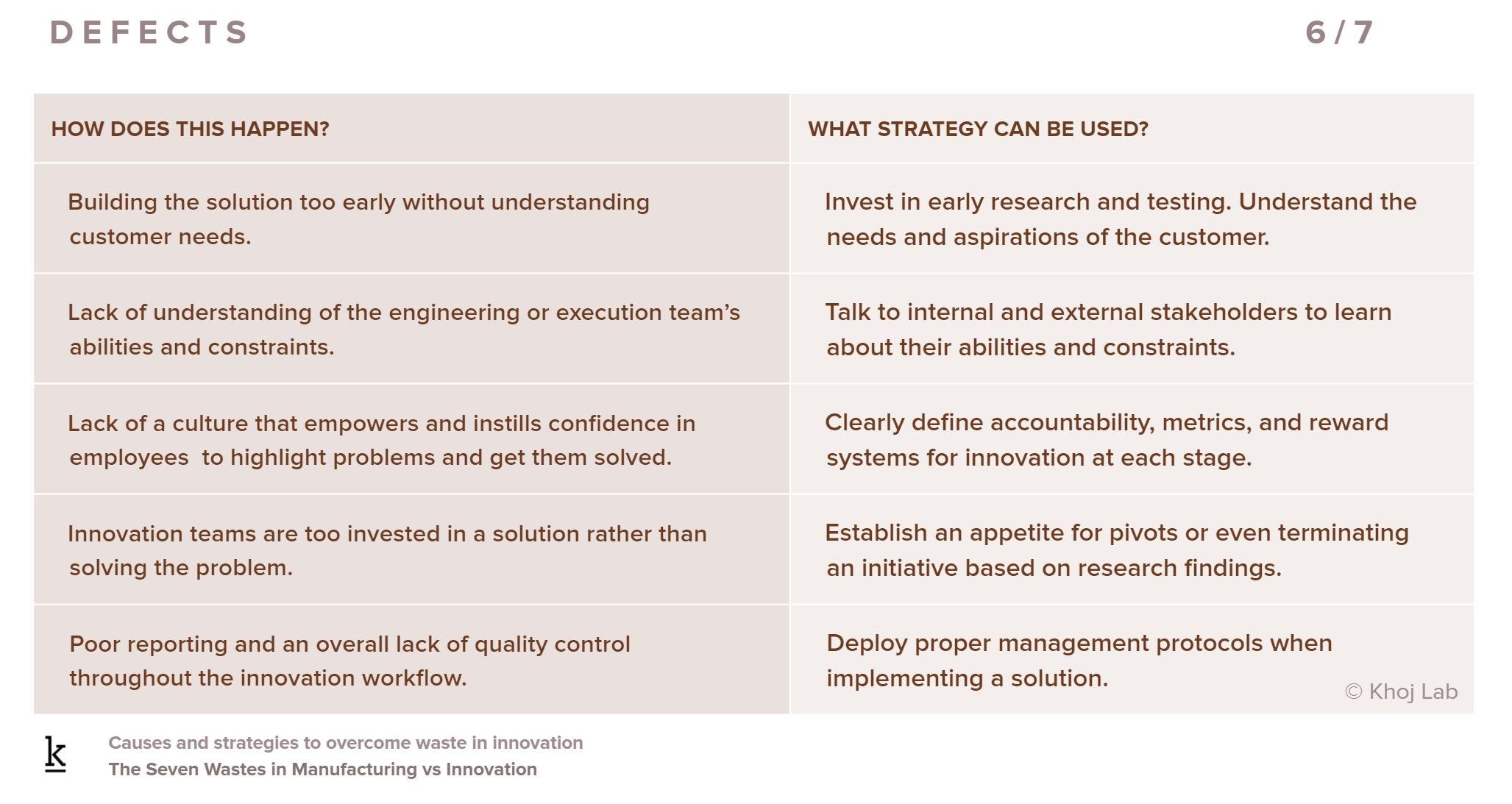

6. Defects

In manufacturing, defects are products that are rejected or fail to meet customer expectations. It often leads to rework of the manufacturing processes.

In innovation, defects are ideas that get rejected, concepts that fail to ship or meet the customer requirements and satisfaction when shipped. A defect can arise in any aspect of the offering — product, service, sales, channel, marketing, branding, customer engagement.

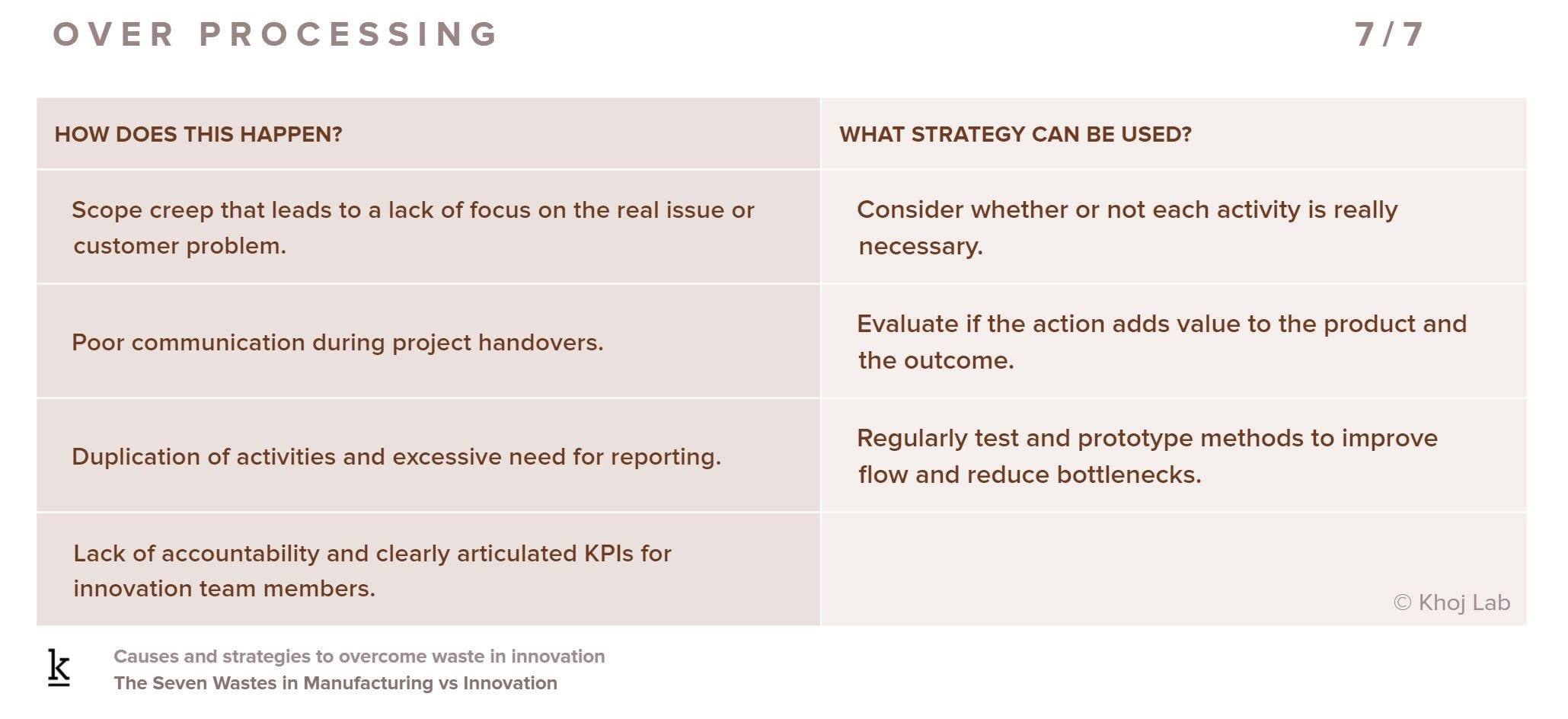

7. Over-processing

In manufacturing, over-processing describes operations beyond those that the process or customer requires.

In innovation, over-processing describes unnecessary activities, scope creeps from stakeholders, misalignments due to poor communication, and overworking on concepts.

To conclude…

The key difference between manufacturing and innovation is in the process itself. Manufacturing strives for perfection and high quality. On the other hand, innovation gets better by failing and testing early prototypes. This is why organizations that are leaders in lean manufacturing and six sigma often struggle to be innovation leaders.

I am not advocating a direct adoption of lean manufacturing principles to innovation but instead learning from it and adapting it. Redundancy and rework are essential parts of the innovation process to build a design that succeeds or at least has a higher chance of succeeding. Borrowing the lens of Muda from lean manufacturing allows us to train ourselves to eliminate waste from our innovation processes. Learning from such imperfections and eliminating such waste helps the idea flow better to its next stage.

Having visibility to the entire innovation process is essential before identifying such issues. Using human-centered design methods can help build innovation protocols, map the flow of ideas and help move ideas across various (internal and external) stakeholders. This is why, at Khoj Lab, we use the learnings across multiple industries and companies to help organizations streamline their innovation efforts with a lean approach to waste removal.

This article is the final part of a 6 part series about innovation flow, which began with my first insight, “Innovation is not ideation.â€

Please follow my stories on Medium. If you have comments, please leave them below or email me directly at shilpi.kumar@khojlab.com.

A special thanks to people who informed my content in this article: Nyurka Fernandes for the illustrations, Anijo Mathew, who helped with editing, Jim Long and other friends/mentors at GE and Herman Miller who informed my thinking and inspired me to write this article.